ROOM

104

Space Lounge

Artistic licence

In honour of the observatory’s 50th anniversary, it

opened its doors and allowed artists to roam free and

install art objects in places of their choosing, from

the astronomers’ village to the observatory itself.

As succinctly put by Simon Mraz, director of the

Austrian Cultural ForumMoscow: “A striking location

was chosen for the observatory, simultaneously

clandestine and providing the clearest, best view

of the stars. And even more remarkable is the

juxtaposition that has resulted - the new observatory

building alongside the ruins of an ancient city.

“I think this collision of ancient history and the

endlessness of space is extremely philosophical

and metaphorical, and is an inexhaustible source

of inspiration for artists. I’m so glad that the

observatory, this centre of science, opened its

doors to allow artists from Austria and Russia to

grasp the vastness of the universe, and also the life

and history of the observatory itself.”

Artists had a unique opportunity to integrate

their works into the surroundings. One particularly

striking art object was Alexandra Paperno’s

‘Abolished Constellations’. Paperno researched

the constellations that did not make it into the

recognised list adopted by the International

Astronomical Union in 1922. Using water-based

paint and small wooden panels, Paperno depicted 51

constellations that date back to the time of Ptolemy,

including the famous Argo Navis constellation,

named after the mythological Greek Argo ship.

The constellations, many of which can no longer

be seen in the Northern hemisphere due to star

shift over time, were then assembled and displayed

in the medieval Northern Zelenchuk cathedral.

The resulting combination of a thousand-year-old

cathedral and the ancient night sky was impressive

to say the least. According to the artist, the

placement of the constellation maps “demonstrated

the link between the scientific and artistic aspects

of the evolution of human thought.”

Ancient origins

Anna Titova’s composition ‘Why Work?’ was dedicated

to the local heroes of Nizhny Arkhyz - Bagrat

Ioannisiani, chief constructor of the observatory,

and archaeologist Sergei Varchenko. Titova’s neon

installation of the wind god Aeolus was located above

a bench in one of the village’s working technical

workshops. Combining a functional workspace and

break room light fixture with a mythological creature,

Titova’s work reflected the ancient origins of the

village in a modern industrial space.

Austrian artists Eva Engelbert created

installations inside the observatory itself.

Engelbert’s ‘Space emblem for GB’ was dedicated

to the Russian space designer Galina Balashova,

who had created the interiors of USSR spaceships,

rockets and space stations, including the original

design for Soyuz-19 and Mir orbital station.

In the dedication of her piece, Engelbert wrote:

“You created a semblance of reality in a fabricated

environment. You built a world in outer space,

from the walls all the way to the emblems on the

astronauts’ spacesuits.”

Balashova (retired since 1990) was instrumental in

both the interior design of the Mir station and the

first landscapes that were sent up into space in the

1960s to alleviate astronauts’ psychological pressure.

One of the most unexpected artworks at the

exhibit was certainly Timofey Radya’s ‘Brighter

than Us’ installation. Set up on a construction

crane in the middle of the field behind the

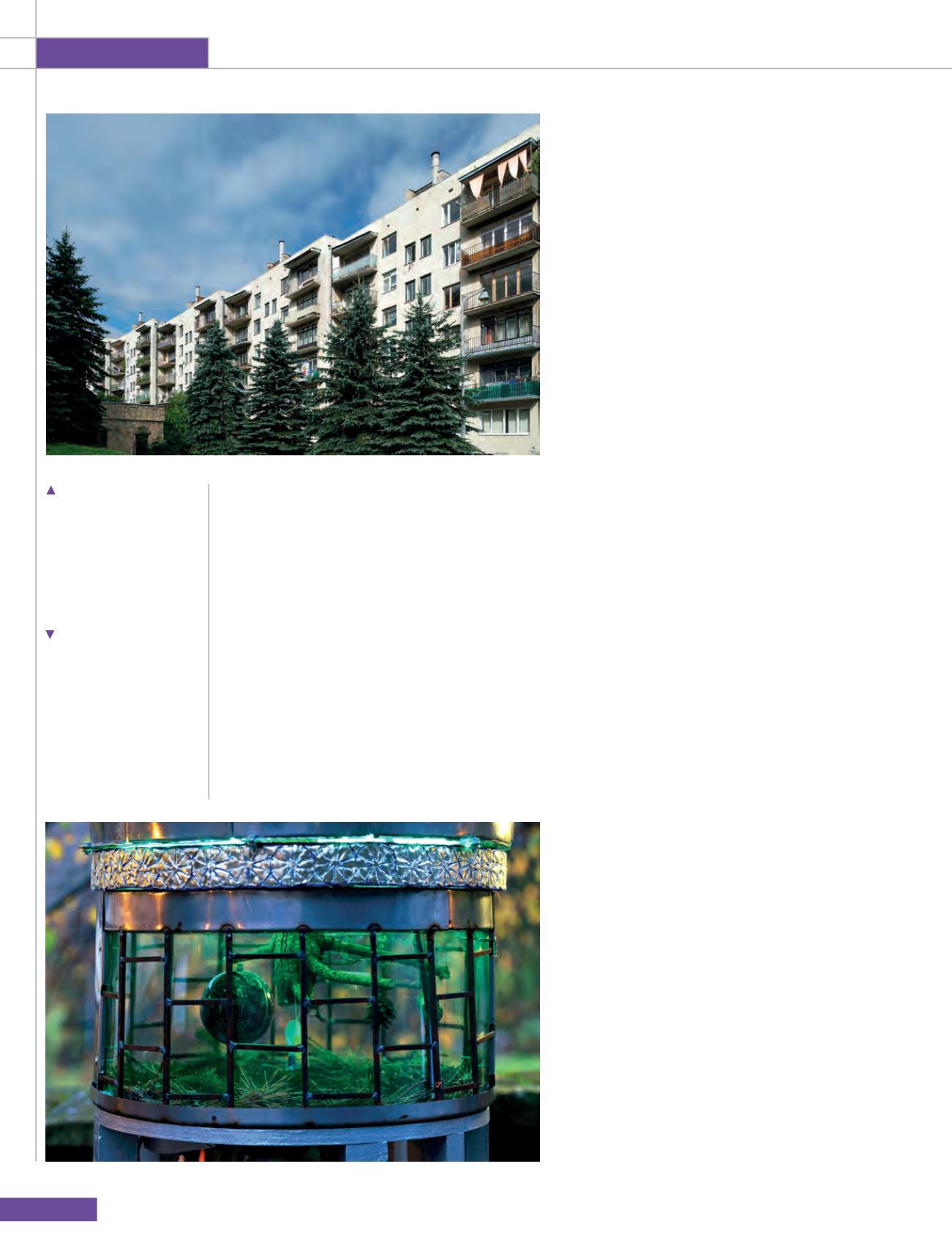

Homes in the city of

astronomers built in a

plain, modernist style.

Yuri Palmin

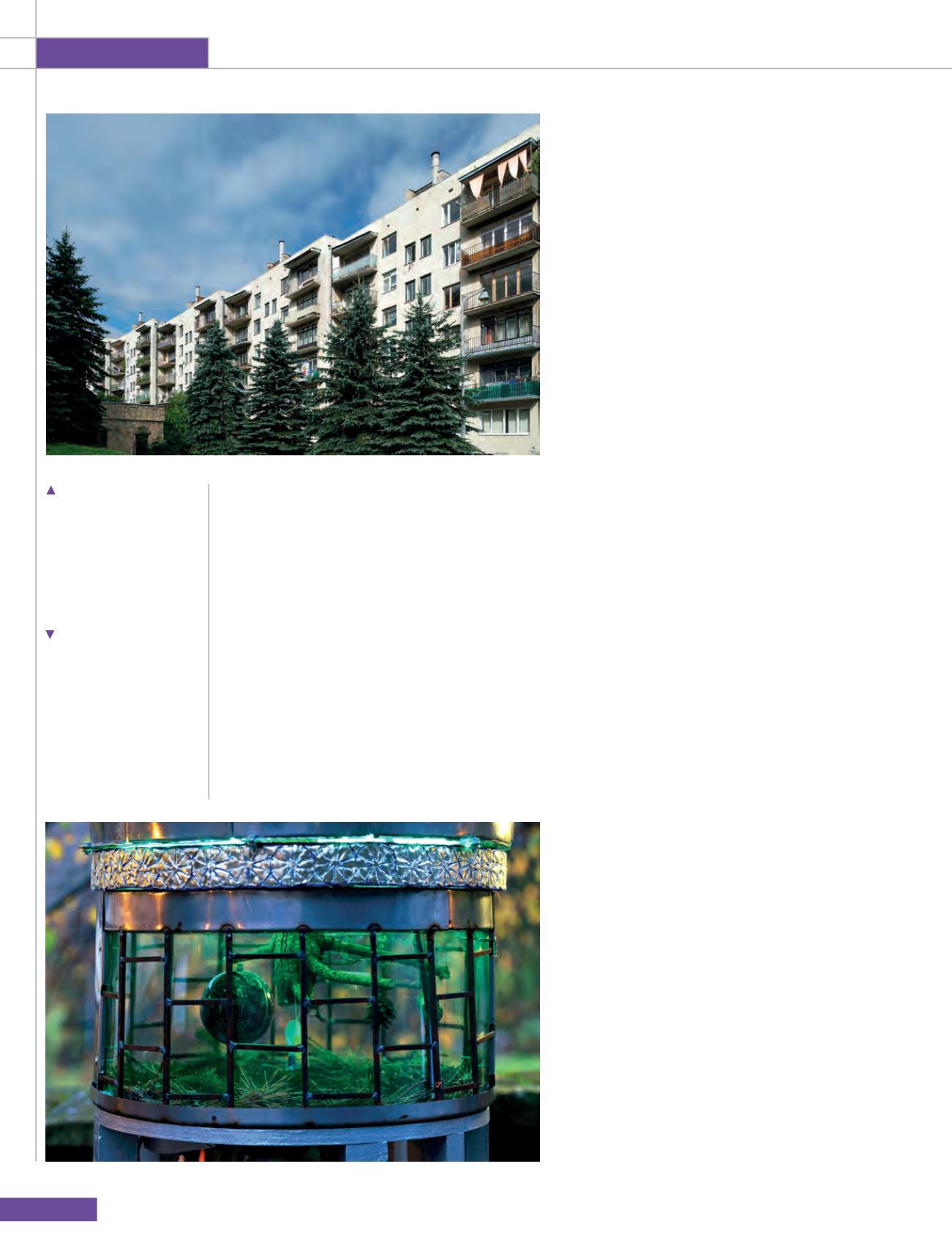

Irina Korina’s

‘Svetilishcha’ (svetilo, a

heavenly body that

radiates light, and

svyatilishche, a sacred

place or altar). Objects

were placed on the streets

of the village and

resemble street shrines,

mailboxes and nativity

scenes.