ROOM

37

Space Security

In the case of the Chinese action, while

much international reaction centred (quite

understandably) on the military consequences,

the additional pieces of space debris caused by

the destruction of the Fengyun FY-1C polar orbit

satellite at such a strategically important altitude

raised significant concerns.

These uncertainties coalesce with other risks

and all point to the need for an institutional

form of space traffic management because the

existing international legal regime does not

address such concerns in anything approaching a

comprehensive manner. Whilst spacefaring States

(and others) are aware of the heightened risk of

space warfare with its adverse consequences

for the already hazardous state of the space

environment, there has not been a corresponding

willingness to either take ‘ownership’ of the

problem or agree to strict, comprehensive and

binding international space rules.

It might be argued that the prevailing ‘soft

law’ and TCBM (‘transparency and confidence-

building measures’) approach to space regulation

may take on an increasing relevance by providing

appropriate international benchmarks, at least

for currently foreseen risks and uncertainties.

However, it is too easy for States not to abide by

the terms of voluntary non-binding instruments.

Not only is the issue of space debris a major

environmental concern, but it also clearly impacts

upon human safety. For example, on 12 March

2009, the astronauts on board the International

Space Station (ISS) were forced to evacuate the

main station and remain in the escape vehicle for

nine minutes, while a piece of debris passed by.

At around the same time, an operational

American commercial satellite (Iridium 33) and an

inactive Russian communications satellite (Kosmos

2251) collided approximately 790 km above the

Earth, resulting in their total destruction. The

collision resulted in approximately 700 additional

pieces of hazardous debris, each with the potential

to cause further decades-long pollution in space.

At a time when it is envisaged that, in the

relatively short term, many more humans

will have the opportunity to go into space

through the development of a commercial

space ‘tourism’ industry, these risks translate

They are not strange bedfellows after all because everything that

we do in space is interrelated with everything else

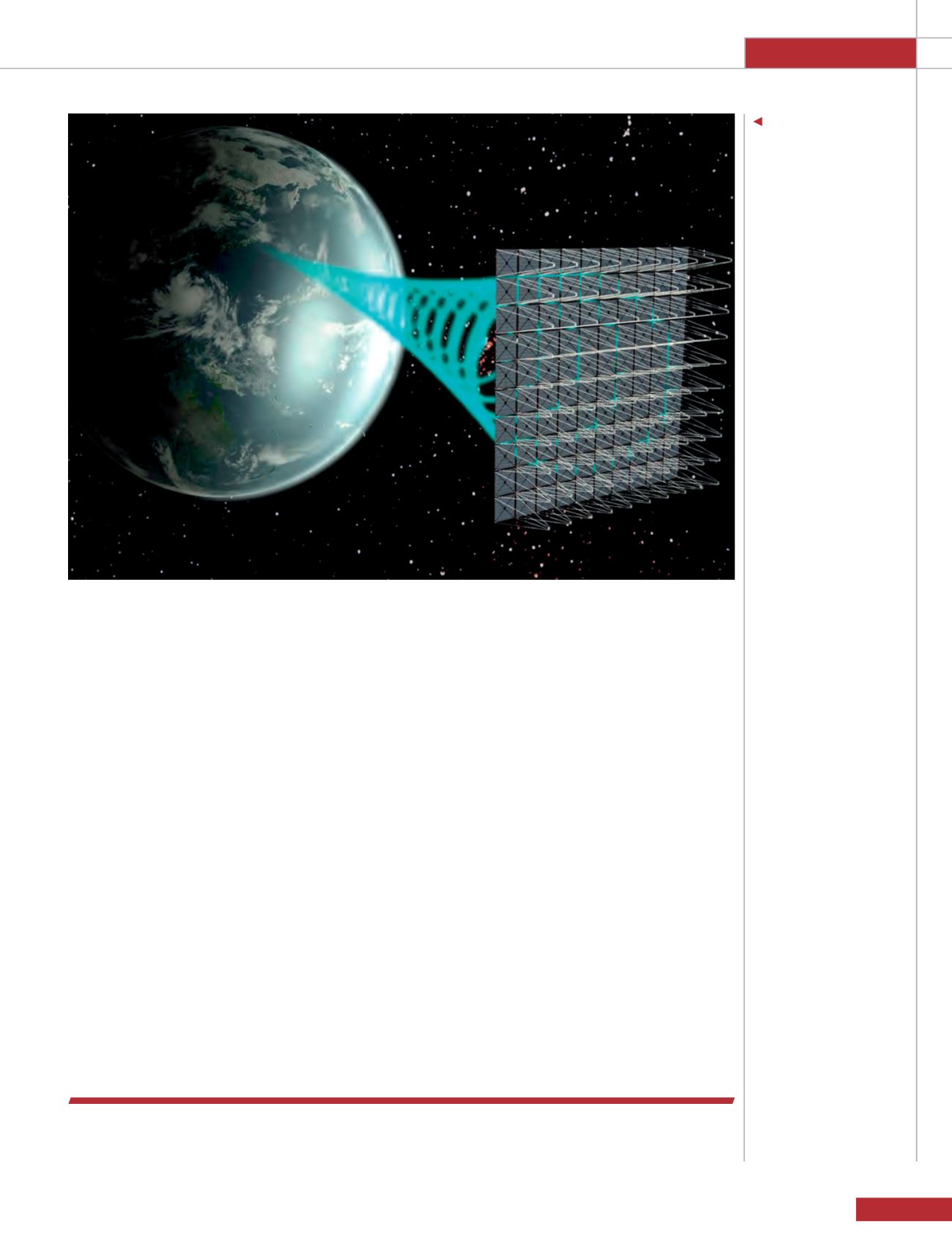

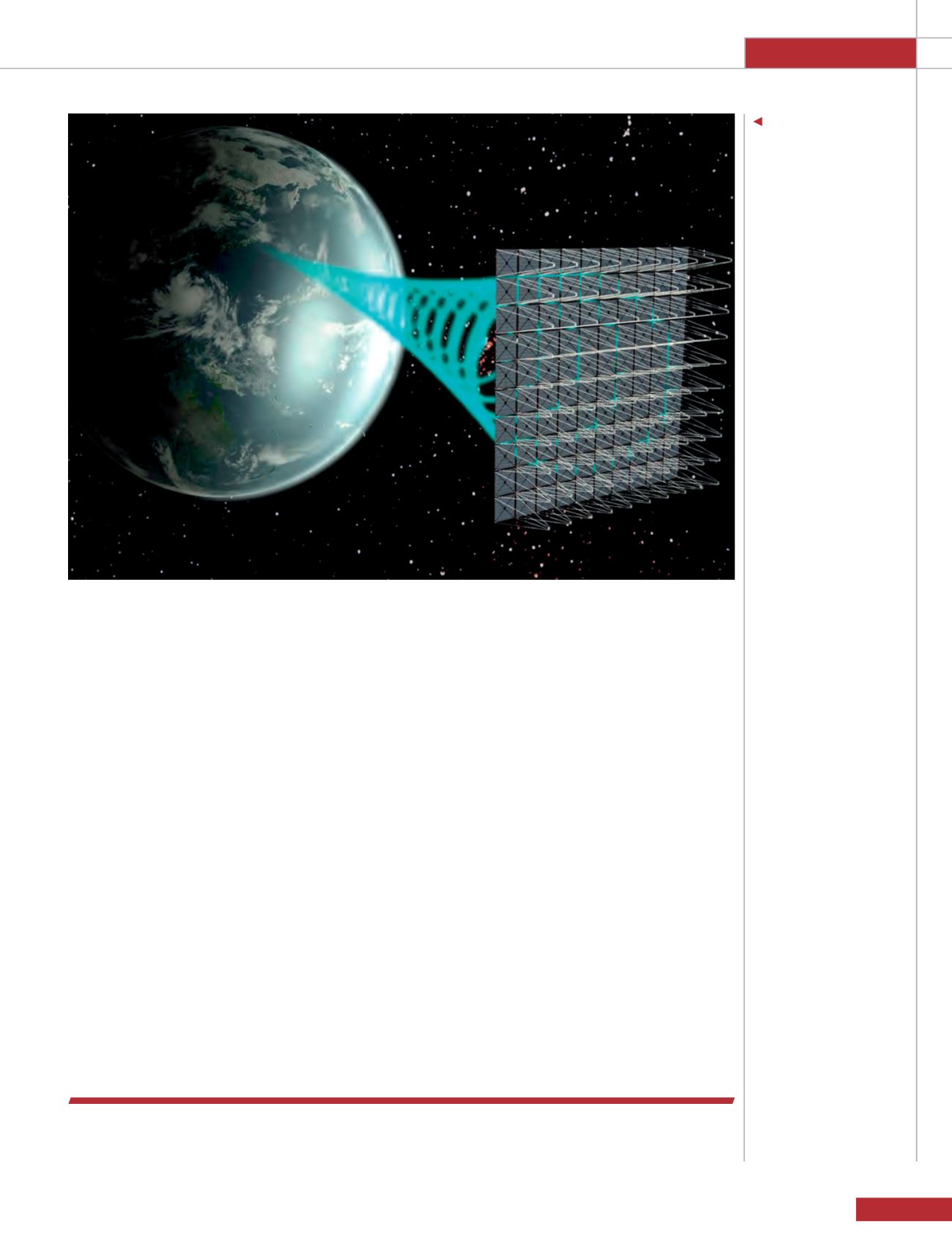

Computer graphic

depicting a future solar

power system in orbit

around Earth, beaming

energy to receiving

antennas on the ground.

As well as technology

hurdles, such systems

will also need to be

subject to specific space

governance issues.

JAXA