ROOM

50

Astronautics

this led to the assumption that one of the most

important factors that influenced the growth and

development of plants in the Svet greenhouse was

high levels of ethylene.

The first measurements of ethylene in the Mir

atmosphere showed an average concentration of 1.1

mg/m³, a perfectly safe concentration for humans.

Higher levels of ethylene in the atmosphere in Earth

control conditions also led to increased tillering

(shooting from the root or bottom of the original

stalk) without changing the plant mass, a shorter

culm and no viable seeds.

The next Russo-American experiment in the

summer of 1997 planned to grow a model short-

cycle plant, Brassica rapa L. in two generations.

And for the first time in history it was a success!

Brassica turned out to be more tolerant to higher

ethylene concentrations in the station’s atmosphere

and it produced viable seeds both in the first space

generation and in re-seeding of those seeds in the

space greenhouse.

Ethylene did, however, cause serious changes in

the plants – all morphometric characteristics, such

as plant height, number of pods and seed mass,

turned out to be half of their Earthly counterparts.

In 1998-1999 we repeated the experiment on

growing two-generation plants on Mir but this

time with wheat – a more interesting plant in terms

of future life support systems. The USU-Apogee

type of wheat was selected for better tolerance

to ethylene and the variety chosen was created

by researchers at Utah State University under

the leadership of Bruce Bugbee, especially for

greenhouses of various bioregenerative life support

systems, including those in space.

Both experiments on Mir resulted in viable wheat

seeds, and the space plants did not differ in their

morphology from the Earth plants.

the Earth control group, with similar low light, the

plants still formed heads, albeit sterile ones without

seeds. This led to the conclusion that some negative

factor had affected the wheat in flight, a theory that

was confirmed by the next experiment in 1996.

This time, the wheat grew and formed heads but

it was obvious from photographs and videos that

something strange was going on with the plants.

When the materials were delivered to the Russo-

American team back on Earth we were all shocked

to discover that in almost 300 fully formed wheat

plants there wasn’t a single seed!

The plants also showed significant morphological

changes. Compared to Earth-control plants the

microgravity plants had almost three times as many

heads, while the culm (stem) was half the length,

the head mass half the weight, the flower head

length was shorter, and there were less spikelets in

a head though the average number of flowers in the

spikelets was higher.

Microscopic cytoembryological analysis of the

biological materials showed that the lack of seeds in

the heads was due to utterly sterile pollen.

Morphological and cytoembryological changes

in the plants that had grown in space were in many

ways similar to the results described in literature on

ectogenous use of ethylene and ethylene-containing

products, which are strong phytohormones, and

During lengthy

flights an

experiment

where

something

is grown can

find a wide

range of uses

not only in

scientific

research

but also for

psychological

support

DEVELOPING TASTE

For the final experiment in the Svet greenhouse on

Mir in 2000, the flavour of leafy vegetables grown in

weightlessness was evaluated by the cosmonauts.

Tasting the greens, cosmonauts Aleksandr Kaleri

and Sergey Zaletin remarked that adding fresh

greens to a crews’ diet would be very desirable,

particularly if they were spicy rather than bland.

Later on, cosmonaut Maksim Surayev wrote about

the lack of flavour: “Roma (Roman Romanenko) was

growing some sort of salad on the space station. And

the salad was so green, Roma obviously wanted to

eat it. I too really wanted to eat it! But back on Earth

they wouldn’t allow it. They said – you have to freeze

it and send it back to Earth for science!

“Imagine this green salad, and two young healthy

cosmonauts staring at it, unable to try it! We decided

nothing awful would happen if we just tried a tiny

piece. So we chewed some. Such a disappointment -

because the greens had absolutely no taste!

“When I was planting my own salad, I found some

wheat seeds that had been left behind by another

expedition and I sneaked them in and planted them

too. But then the scientists from Earth told me to get

rid of the wheat.

“I’m sorry, dear scientists, I couldn’t do it – it was

growing so beautifully! Just look at the heads on this

wheat! And I really do hope that they turn out tastier

than Roma’s salad!”

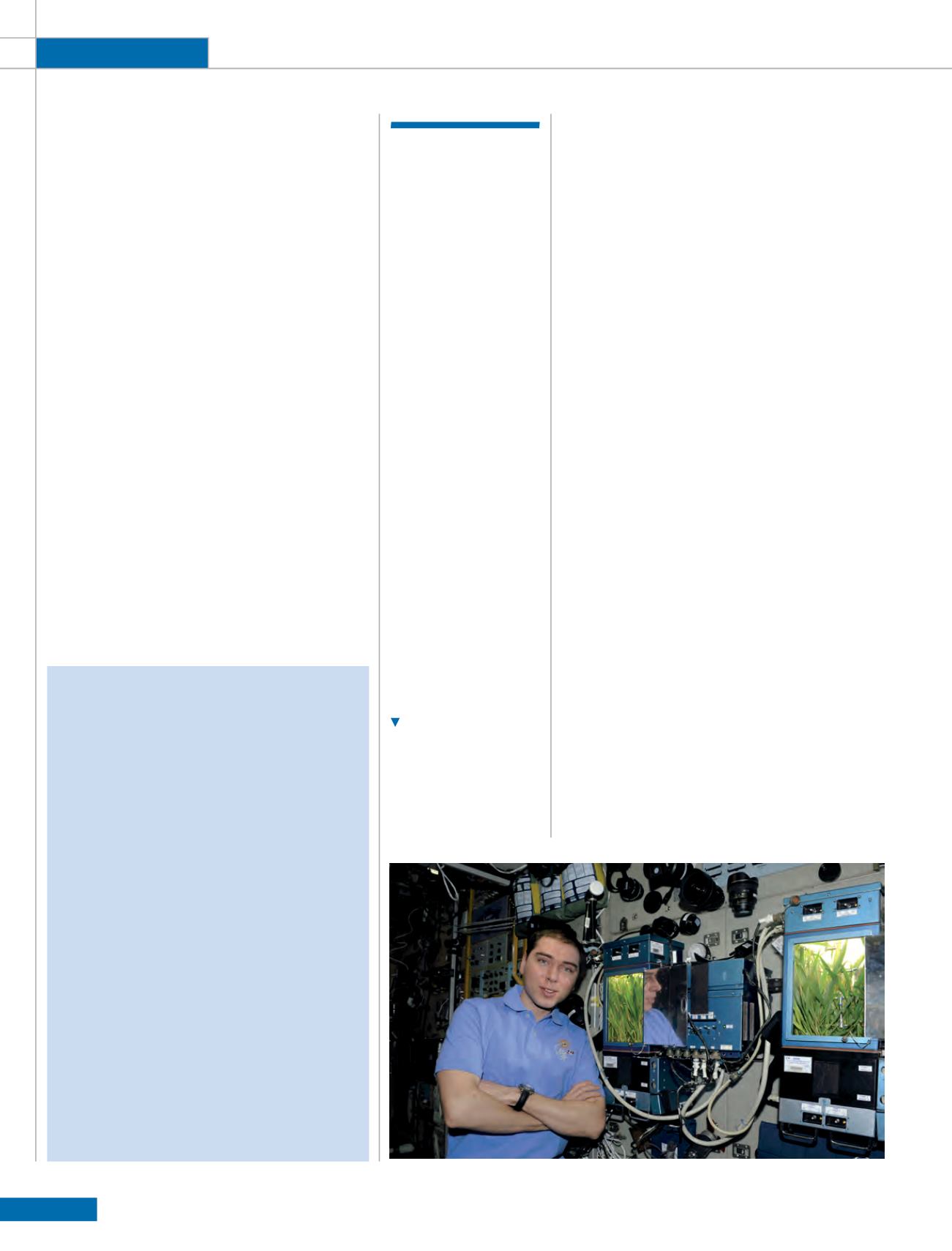

Cosmonaut Sergey

Volkov, the seed-to-seed

cycle of the super-dwarf

wheat growing

experiment in the ‘Lada’

greenhouse on the

International Space

Station in 2011.